Freed through comedy, Tanael has dream in hand

As an immigrant pursuing his dream, Tanael Joachim is using comedy to pay his rent and to make people happy.

He performed his second standup special “Haitian Dreams” in Miami, back in August.

On stage, at the Fantasy Theater Factory at Sandrell Rivers Theater that evening, there was much sitting room. The budding comedian touched on topics like why some people are considered “heros”, Haitian-American belonging, and the realization of being a descendant of enslaved people and its connection to South America. In reference to the latter, he teased that people in South America woke up with a bad case of “the Spanish”.

“The show is meant to be universal,” said the comic in an interview with AyiboPost.

This special is also the source of the popular clip you may have seen around social media, where he jokes that the French language is only present in Haiti because of a foreign exchange program called “slavery”.

While plenty of laughs reverberated throughout the room, there were only 30 spectators in the 172-seat theater.

And though Joachim strives to fill every seat at his shows, he insists that his job is to perform to the best of his ability regardless of the number of people in the audience, and says he wouldn’t enjoy a show if the audience weren’t enjoying themselves.

As for the turnout, the funny man doesn’t blame the theater, adding that they did a great job.

Screenshot 2023-08-13 8.36.43 PM – A screenshot from Tanael Joachim’s first special called JANUARY 3RD on Netflix.

According to a spokesperson for the Fantasy Theater Factory, an interview on NBC6 was coordinated, a press release was sent to the company’s database of 600 media contacts, and even though marketing is not obligated for renters such as Mr. Joachim, some promotion is done for every client.

There are posts for the show on the Sandrell Rivers Theater’s Instagram page but not on the Fantasy Theater Factory page – the latter of which is a production company for shows throughout Florida primarily for families and children. The spokesperson confirmed that this is how things are typically done.

Prior to the show in Miami, Joachim performed “Haitian Dreams” in Austin, Texas; Boston, Massachusetts; and Montreal, Canada. In September and October, he took to the road, traveling to 13 countries in Europe, including a finale in Istanbul, Turkey before returning to New York.

Read also : À 20 ans, Festival Quatre Chemins dévoile sa «formule magique» de longévité

For this rising star, traveling for comedy came many years after his immigration to the United States in search of better educational opportunities, and it took a while before he could even manage to scrape up enough money to cover his rent through this notoriously difficult profession. But, intent on this dream, Joachim left college and set his site on stand-up comedy.

However, as an immigrant, Tanael’s journey starts in Gonaives, before arriving in America at the age of 19.

He understood that his upbringing in Haiti would be of interest to Haitian-Americans because, in their case, they are born in the US of Haitian descent and don’t know what it’s like living in Haiti.

“They get the best of Haiti while living in America, and aren’t exposed to the worst of Haiti,” he says.

Around the age of 14 or 15, he says he did not go to school.

“I could not think of one year where I went to school for the entire calendar year,” Tanael says.

But his parents were committed to his education.

He adds that they insisted on it. To them, education is the only way to make something of oneself. Not necessarily a formal education such as a college degree,but understanding how life works, knowing how to read and write, knowing there is more access to information with libraries and the internet which supports learning.

While still living in Gonaive, Tanael’s parents sent him to kindergarten at L’abc Joyeux, then College Saint Paul, and an all-boys Catholic school called Ecole Cirguillot. For middle school, he went to Collège Immaculée Conception.

Later, in Port-au-Prince, he went on to pursue his secondary studies at Institution Saint-Louis de Gonzague where he started learning English.

In 2008, Joachim left Haiti for Adelphi University in Long Island in pursuit of a degree in business administration.

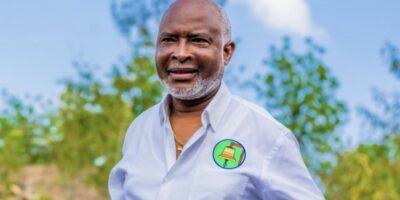

Tanael Joachim on stage

Two years into his studies, the 2010 earthquake took place triggering an existential crisis for him. The sight of such destruction in seconds left a profound effect, which got him to really focus on what he really wanted in life.

“I realized life is a little too fleeting,” Joachim says, eventually withdrawing from Adelphi and resolving to move forward with comedy.

Working in New York between 2008 and 2012, he focused on speaking better English. Through television, books, and conversation, he manages to improve and to get a better grasp of things in the United States. Though it took many more years for comedy to pay the rent.

Unemployment, race, and class all played a role as the aspiring comedian worked his way toward increasing his income to avoid losing a shelter over his head.

From helping troubled youth at a wilderness therapy program, to working with a broker in a real estate office — cruising the streets of Manhattan as an assistant and a bike messenger (avoiding a few close calls with cars along the way) – his road to success is paved with a wide range of experiences.

But, following the earthquake and for much of the time before his career in comedy became more and more dependable, Joachim mostly worked as a handyman, thanks to the skills he acquired in his youth growing up around masons and carpenters.

That time was filled with insecurities, from not having health and dental coverage, to not knowing if more work would come as the days went on.

He worked as a handyman by day and performed comedy by night at open mics and clubs, mostly for free but nothing at a livable wage.

While relying on a day job to cover his living expenses, the happiness the budding comedian drew from his early work in comedy only grew.

He describes comedy as a freeing experience, where the comedian gets away with something. While the jokes make strangers laugh, the comic’s “ego is fed”, he explains.

To him, a dream does more than make someone happy, it does not harm anyone, and provides some value to the world. There might be people who go out there to offend others in this field but at the core of being a comedian, that’s never the end goal. For him, Tanael says, it doesn’t feel good to offend people.

“It’s a fun thing to be funny,” he adds.

In terms of inspiration, Tanael Joachim cites George Carlin as daring and among his favorite comedians — and finds himself among other Haitian stand-up comedians including Garihanna based in Montreal, Sejoe in the New York and New Jersey area, Success Jr. in South Florida, Plus Pierre based in Florida, and Ti Inosan based in New Jersey.

Historically, American stand-up comedy is tied to minstrel shows where White people would ridicule Black people -– perpetuating stereotypes of African Americans, using burnt cork to paint their faces, exaggerating the eyes and lips of their character which became known as blackface.

Read also: De quoi vit un.e comedien.ne dans ce pays ?

The caricature of a Black man, Jim Crow, became a common character in minstrel shows.

Many stereotypes against Black people came from minstrelsy. Despite blackface’s repeated occurrences, minstrel shows were said to decrease as vaudeville performances increased and maintained popularity from the 1890s to the 1930s.

Comedic performances also took place in burlesque shows, saloons, and music halls.

With the roots of comedy’s talent base and tools expanding, burgeoning comics have had more to consider in their work.

After vaudeville, without a set of established norms, comedians invested more of their time in performance, emphasizing delivery and timing, as text was easy to steal.

Later in the 1960s, norms like the acknowledgement of talent and experience contributed to delivery, and comedians such as Chris Rock dedicated more time to writing.

Key elements such as timing, writing, delivery, and voice play a central role in Joachim’s work today — notably his foreign exchange program joke.

But, Joachim says, a joke can’t be explained or the magic is gone.

No subjects are off limits in comedy. Even being Haitian can be made fun of, he adds. That is, if the person can do it well.

“I don’t think there’s a line, that’s the purpose of comedy, anything that happens in life can be made fun of,” Jaachim says, adding that the audience decides if it’s funny or not.

Tanael Joachim on stage

Stand-up comedy is the most direct form of communication, he argues — more than singing, rapping, playing instruments and spoken word. The audience either laughs when they hear the joke or they don’t.

“Haitian Dreams” is Joachim’s second special recorded in front of a crowd. The first, released in 2020, dubbed “January 3rd”, is available on Amazon Prime and titled after the comic’s birthday.

In this special, he explores topics like English as a third language, race, and the Me Too Movement.

The Me Too movement was spearheaded by Tarana Burke to demand that rape or assault victims be believed, and for those who commit these crimes to be held accountable. Most victims suffer at the hands of intimate partners, or family members. The perpetrators are often protected by rape culture, in which individuals, families and communities diminish the severity of violence and abuse against women to protect the men who commit these acts.

In his eyes, Joachim explains that The Me Too movement exposed the depravity in protecting men from the consequences of their crimes — even the perversion that occurs at different levels — from outright attacks, to making women feel uncomfortable in public spaces.

A mirror is held up to men, Joachim adds, to do what he refers to as “creep-management”.

“Men have to be way less creepy so when you go out in the world you’re not seeing women as objects,” Tanael says.

On stage in Miami, Malala Yousafzai is a hero and Greta Thunberg is not, and a person being misgendered is not as traumatizing as seeing a dead body burned to the bones, says Tanael.

However, he declined to answer any questions about the humor behind his jokes.

Before declining, he went on to say that the more serious a topic, the more a person should try to find the humor in it to defuse its power and make it manageable.

In “January 3rd” he also explores race as it relates to Haiti, noting that the country may be thought of as very pro-Black, but the identity in Haiti is not Black. In Haiti, Haitians seldom, close to never, think of themselves as Black people.

Read also: Échanges à Paris avec l’humoriste Haïtien Christolin Rodlin

It is following his move that the realization became apparent to Tanael, how race is connected to so much in the United States.

“There are certain rooms in Brooklyn where there are only Black people, like Moe’s and Essence, other rooms are mainly white people like the ones in Williamsburg, the Upper East Side or the Upper West Side,” he says.

The difficulty of life as an immigrant also comes to mind, Tanael says, notably the debt he feels towards Haiti — which helped him become the citizen of the world he sees in the mirror today.

As an outsider, the comedian has a front row seat to the later stages of gentrification.

He has limited observations when it comes to Brooklyn’s transformation, since his life in New York started after the gentrification of the 1980s and 1990s, however, what occurred is still ongoing and affects life for this transplant.

A part of the racial discussion for Tanael is white-liberal pity, when white liberals think it’s up to them, specifically, to save Black people.

“It tries to be compassionate but it’s really condescending,” he says.

The budding comic’s struggle through the immigration system in America included getting a student visa, a work visa, becoming a green card holder, though, technically, called a “permanent resident of the United States of America.”

In the US, after leaving Haiti where his brother remained as a teenager until his late twenties, Joachim says he would try to think of a way to save Haiti.

“I used to feel guilty,” Tanael says. “You can’t save people. Haiti didn’t become what it is because of me.”

Even with Haitian sketch comedians such as Jean Claude Joseph, Papa Pierre and Tonton Bisha performing in Haiti, Tanael believes having migrated to America is what opened the door to comedy.

In 2008, Haiti was better off economically compared to 2023, yet President Rene Preval said Haitians would have to swim to get out of the country — a testament to how helpful Preval understood the Haitian government would be. Haiti’s issues would have been more pressing in life, Tanael says, and comedy could only have been done at a small scale and without a path to making money.

He even jokes about being an immigrant in comedy, since this dream came to him later in life, with no aspirations of being a comedian growing up.

Without any regret for leaving Haiti for the sake of pursuing a dream, Tanael says if he had decided to stay in Haiti perhaps there would be work with the parents who raised him — and medical school being a possibility.

“If I was still in Haiti, I’m almost positive I would not be doing comedy. I don’t feel sad about it. I feel very lucky I get to do comedy,” he says. “That’s the thing I really enjoy in life, that’s the craft I love. I love the fact of being in America where I can chase a dream like that.”

Cover Image : Screenshot 2023-08-13 8.36.43 PM – A screenshot from Tanael Joachim’s first special called JANUARY 3RD on Netflix.

Stay in touch with AyiboPost through :

► Our WhatsApp channel : click here

► Our WhatsApp Community : click here

► Our Telegram canal : click here

Comments