The Power of Social Movements and the Struggle Against Corruption and Impunity in Haiti

“This country is a heritage site.”

The discordant hum that resonates from the conch shell has a ceremonial tonality that distinguishes it from any other sound. In Haiti, it recalls the spirit of a revolution born out of a mass uprising of enslaved people who, in 1791, literally set ablaze the infrastructure of the most lucrative slaveholding colony in the French Caribbean.

The insurgents forged their own independent nation from the flames of colonial ruin. In the Champs de Mars, the central square in Haiti’s capital, Port-au-Prince, stands the resolute figure of the Nèg Mawòn: a sculptural homage to the unknown maroon rebel who sounded the clarion call to rebellion by blowing into such a conch, or lambi in Haitian Kreyòl, and setting into motion a chain of events that had reverberations across the entirety of the slaveholding world.

It is this same haunting sound that captivates our attention in the opening sequence of Etant Dupain’s new documentary film The Fight for Haiti, as a man caught up in the carnival-like atmosphere of popular protest on the streets of the city overlooked by the ancestral juggernaut of the Nèg Mawòn blows into a lambi to amplify the revolutionary soundscape.

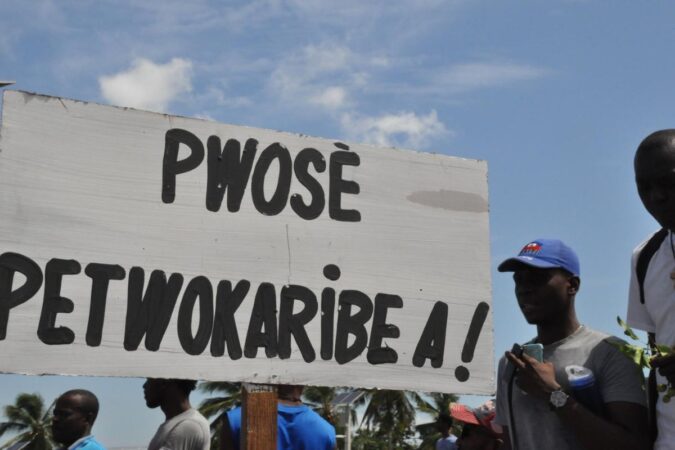

Protest against corruption and impunity, June 9, 2018. Haiti, Airport Junction. © Etant Dupain

Brought to life by the team behind the award-winning film Madan Sara: Pouvwa Fanm Ayisyen, The Fight for Haiti represents an important intervention, spotlighting the people’s fight against the entangled web of corruption and impunity orchestrated by Haiti’s key power brokers and facilitated to varying degrees by the international community—especially by the “Core Group”, whose dubious vested interest in Haiti is held up to critical scrutiny by Dupain’s interviewees.

Read also : Le CORE group n’existe pas juridiquement

This is the fight of a popular movement that has, since at least 2018, been seeking justice and accountability for the squandered and embezzled funds that were designated for regeneration projects in Haiti as part of the PetroCaribe agreement.

But as Dupain masterfully demonstrates, this spirit of protest and the refusal to accept terms of oligarchic domination are part of a proud cultural inheritance of the Haitian people and a reminder that as one interviewee states, “the masses never lose”.

Kot kòb Petwo Karibe a?

Protest against corruption and impunity, June 9, 2018. Haiti, Airport Junction. © Etant Dupain

Launched under the leadership of Venezuela’s then-president Hugo Chávez in 2005, the PetroCaribe agreement enabled member states who were part of the alliance to buy oil from Venezuela under favourable financial terms, paying only a portion up front with the remainder being repaid after a number of years.

With the savings generated from this beneficial agreement, signatories agreed to channel investment into social services and critical infrastructure.

For Haitians, the scheme presented opportunities for improved wellbeing and economic self-determination in a nation that has been both the prey of colonial and neocolonial forces and rendered a pariah state by those colonial forces for daring to stake its own anticolonial revolutionary claim to independent statehood.

This claim was, as Dupain asserts, “contrary to the white supremacy narrative” authored by the western world. Given the wide-reaching benefits that it promised, therefore, there was a lot of international pressure placed upon Haiti not to sign the agreement to begin with—and as Dupain’s film makes damningly clear, it has never been in western interests for Haiti to succeed, because a “successful Haiti would be a blow to the white supremacy narrative”.

The biggest failure by the international community in the context of the PetroCaribe scandal, however, is that it has failed to hold successive corrupt administrations to account for crimes that have been perpetrated against the Haitian people, propping up nefarious presidents and, in the majority of cases, literally installing them into public office (often against the will of the majority of Haitians desperate for accountability and democratic due process). The Haitian people have nevertheless shown an unrelenting determination to create their own narrative and demand change.

Fast forward a decade after the PetroCaribe accord was signed by then-president René Préval to 2016, when Youri Latortue, Chair of the Haitian Senate’s Ethics and Anti-Corruption Committee, released a report that revealed widespread corruption at senior government level and the misappropriation of funds associated with the PetroCaribe programme.

successful Haiti would be a blow to the white supremacy narrative

Growing awareness of this report ignited a social movement that spread rapidly across social media channels. Its power was rooted in the simplicity and clarity of a collective demand: Kot kòb Petwo Karibe a? Where is the PetroCaribe money?

Protest against corruption and impunity, June 9, 2018. Haiti, Airport Junction. © Etant Dupain

The self-professed “Petrochallengers”, the activists who are at the forefront of the “fight for Haiti” and the protagonists of Dupain’s documentary, have made the PetroCaribe scandal their cause célèbre, forging a powerful and ever-expanding collective, and demonstrating the power of citizen-led resistance to high-stakes corruption and impunity. This is a movement that has made a “lifetime commitment” to the fight against institutional misconduct, according to interviewee Velina Elysee Charlier, Haitian feminist, human rights activist and member of the Noupapdòmi (literally translated as “we will not sleep”) collective. It is a long fight and a slow fight, but, in Charlier’s estimation, it is a fight that is worthy of great sacrifice, because if “you believe in justice and injustice hurts you to the core” then “that’s why you fight for justice—to end corruption and impunity. And because you know that as long as some of us aren’t living well, none of us will live well. Because well-being is a collective matter, and it is a fundamental right.”

Read also : Le procès PetroCaribe peut-il encore se tenir ?

“We are fighting for our lives”

In taking up this challenge, however, dissidents also take on great risk. In the years since the citizen-led movement against corruption and impunity was formed, increasing “gangsterisation” in Haiti’s capital (and indeed beyond) has been overlooked and—according to many Haitians—actively shepherded by the Haitian government in a bid to distract ordinary people from the scandal. This is described by Dupain’s interviewees as a form of “state-sanctioned insecurity”.

Consequently, the fight has shifted: it is not only a fight against injustice, but a fight for survival. As one interviewee attests, “we are fighting for our lives”. Affecting footage of the eulogy given by the sister of murdered activist Antoinette ‘Netty’ Duclaire who was “likely targeted for [her] human rights work and [her] pursuit of truth” according to Amnesty International’s Americas Director, highlights the real human consequences of demanding justice and accountability within this context of state-sanctioned violence that has been left to go unchallenged and unpunished.

Such moving personal testimonies are the pivot-point upon which Dupain’s compelling narrative hinges, taking his audience closer to the affected individuals and centring the voices of the actors on the inside that western media reports repeatedly overlook.

Though the rampancy of gang-led violence has captivated the focus of many media headlines, the stories that follow them are so often couched in terms of humanitarian crisis, demonstrating a perfunctory interest in its root causes and redeploying familiar racialised tropes of “Haitian misrule” inherited from colonialism.

Moreover, while various international solidarity movements have responded to the growing security crisis in well meaning attempts to “Free Haiti” through hashtags, the viral momentum created by such campaigns has failed to meaningfully flip the media narrative or prompt engagement with Haitian voices that are being systematically silenced.

And in this moment, Haitian voices are being tuned out once again in heavy-handed attempts to restore order through a wildly unpopular multinational security mission led by Kenya and sanctioned by the UN. As The Fight for Haiti demonstrates, such foreign “interventions” have a history of failure. In Dupain’s words, “only Haitians can free Haiti; no one else”.

Read also :L’accord complet signé avec le Kenya pour la force multinationale

Haiti beyond the headlines

In producing this film, Dupain’s mission was therefore “to take everyone beyond the headlines of Haiti: gang violence in Haiti; corruption in Haiti; assassination Haiti. Because this is what people see about Haiti. These are the headlines of every article from mostly western media about Haiti.” It is as much a call to action as a call to attention: we are encouraged to listen and learn and to wake up from our collective slumber of ignorance and apathy. In this way, the pronouncement Nou pap dòmi is not only for Haitians, but for all of us. “I think people should do more to learn and to educate themselves [about Haiti],”

Protest against corruption and impunity, June 9, 2018. Haiti, Airport Junction. © Yvon Vilius

Dupain urges, “but it’s a lot to ask sometimes when the whole world is on fire. So, I wanted to add something to the conversation where people can actually learn something if they put one hour aside.” The result is a masterful affirmation of this goal. The Fight for Haiti encourages its audience to dig deep, and to ask difficult questions of themselves and the international institutions complicit in upholding corruption, impunity and gang violence in Haiti.

It also demonstrates the agility and resilience of the fight—a fight in which the film plays an integral role by clearing a pathway for narrative interventions that centre voices, stories and individuals which can help to start progressive and respectful dialogues, with Haitian people at the front and centre.

As Dupain attests, “the film is for the movement. Because the more tools we have, the more stories that we have out there, the more I believe we will be able to reach more hearts and souls to be able to do something.” Those that enter screenings of The Fight for Haiti will leave richer in understanding and most certainly ‘awoken’.

By Nicole Willson

Cover image | Protest against corruption and impunity, June 9, 2018. Haiti, Airport Junction. © Etant Dupain

A limited screening of The Fight for Haiti and Q&A with the filmmaker Etant Dupain will be taking place at the Bloc Cinema at Queen Mary University of London on Tuesday 19 November at 6.00pm.

To register for the event, go to: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/free-screening-of-the-fight-for-haiti-live-qa-with-etant-dupain-tickets-1037802504227?aff=oddtdtcreator.

If you are interested in hosting a screening of The Fight for Haiti, contact thefightforhaiti@gmail.com. To support free public screenings of the film in Haiti, you can make a donation via https://thefightforhaiti.com/support.

Dr Nicole Willson is a Leverhulme Trust Early Career Research Fellow at the University of Central Lancashire currently working on a research project on Haiti’s women revolutionaries.

► AyiboPost is dedicated to providing accurate information. If you notice any mistake or error, please inform us at the following address : hey@ayibopost.com

Keep in touch with AyiboPost via :

► Our channel Telegram: click here

► Our Channel WhatsApp: click here

► Our Community WhatsApp: click here

Comments