At 76, this energetic man continues to work in his workshop, where he repairs, designs and brings to life new accessories, shoes, sandals and more.

Based in Haiti for almost half a century, Nigerian Sakariyawu Ligali, nicknamed ‘Bob Africain’, tells AyiboPost about this proud and nostalgic part of his life.

“Despite everything that is said about Haiti, despite everything that’s happening, I was able to forge my place here and build my life,” declared Ligali, interviewed by AyiboPost in his Turgeau workshop in early December 2024.

An artisan, Ligali arrived in the country in the early 1970s.

In the Turgeau neighborhood, at the corner of Rue Baussan and Jean-Paul II, his home catches the eye.

Transformed into a teeming workshop, there are piles of scrap metal, large sewing machines from a different time, assembly tools for shoemaking, leather skins, and a multitude of shoemaking accessories.

The space is overflowing with stories and bears witness to the rich and unique life of Ligali, a former technician in the embroidery industry.

“Everyone knows me here by the nickname ‘Bob’, ‘African’ or ‘African Bob,’” he explains with a smile reflecting his familiarity and his notoriety in the neighborhood.

At 76, the energetic man continues to work in his workshop, where he repairs, designs, and brings to life new accessories, shoes, sandals, etc.

Sakariyawu Ligali’s former workplace in his workshop. December 2024 | ©Lucnise Duquereste

The story of his life is heavily marked by exile.

It all began in 1948, in Lagos, in the southwest of Nigeria, where Sakariyawu Ligali was born.

From a young age, he had a passion for technical professions, inspired by his father’s profession in haute couture.

This is why, once his studies were completed, he turned to embroidery and leather work.

His journey took a decisive turn during the Nigerian Civil War, between July 1967 and January 1970.

This deadly conflict pitted the Nigerian government against the secessionist region of Biafra.

Fueled by ethnic, political, and economic tensions, this conflict caused hundreds of thousands of deaths and massive population displacements, leaving deep scars in the country’s history.

Fleeing the violence, the young Ligali left his native country to take refuge in Senegal.

His journey took a decisive turn during the Nigerian civil war, between July 1967 and January 1970.

There, he put his skills to good use working as a trainer in an embroidery factory.

But his enthusiasm for learning does not stop there.

He then flew to Paris in 1968, where he began studying drawing and industrial art.

A year later, these training courses led him to pursue his dream in the United States where he deepened his know-how in technical and creative areas of the industry.

It was through work that Ligali discovered Haiti in 1971, aged 23 at the time.

Production of an orthopedic shoe. December 2024 | ©Lucnise Duquereste

Solicited by Haitian entrepreneurs of the time, such as Marc Désert and André Apaid, he was recruited for his skills in the field of subcontracting.

“I was going back and forth a lot between Haiti and the United States, but at one point, I decided to settle down here permanently,” he confides.

“When I arrived, it was a time when there were a lot of opportunities in crafts in Haiti,” Sakariyawu Ligali tells AyiboPost, with a hint of nostalgia in his voice.

I was going back and forth between Haiti and the United States a lot, but at one point I decided to settle down here permanently.

Upon his arrival in the country, although he did not yet master Creole nor was he fully integrated into Haitian society, Ligali quickly made a name for himself.

His creations, particularly his women’s shoes, very fashionable at the time, quickly attracted a loyal clientele.

“My work was in high demand. Demand was high, which allowed me to produce a lot and meet customer needs,” he explains.

Bob African did not just produce; he also shared his know-how.

He says he trained local artisans to make new styles of shoes and sandals, innovative models that were not yet common in the local market.

“I wanted to pass on what I knew and help develop local crafts,” he remembers with pride.

He says he trained local artisans to make new styles of shoes and sandals, innovative models that were not yet common in the local market.

In 1974, Ligali decided to leave the factory where he worked to settle permanently in Haiti and open his own workshop.

The choice of location was daring: in Turgeau, far from the commercial bustle of the Grand-Rue, where the majority of entrepreneurs of the time were concentrated.

View of the facade of Nigerian craftsman Sakariyawu Ligali’s workshop in Turgeau, Port-au-Prince, in December 2024.| ©Lucnise Duquereste

“I was the first to open a store here,” he emphasizes.

“The area was not yet developed, but I persisted and worked hard to build something lasting. »

His workshop, still in operation today, witnessed many significant events of the time.

Ligali remembers with emotion the exhibition fairs on the Champ de Mars and the presentations under François Duvalier’s dictatorial regime, where his creations were very appreciated.

“It was a period when Haitians consumed a lot of what was produced locally. The professionals were motivated and proud of their work,” he explains.

His workshop, still in operation today, witnessed many significant events of the time.

However, like many professionals, Ligali has seen his activity affected by the economic and social upheavals in the country.

From the 1980s and 1990s, the massive influx of foreign products considerably weakened local production, particularly in the field of shoemaking.

This influx of foreign products on the local market takes place in a context where the Haitian State had signed – at the beginning of the 1980s – a set of agreements with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank.

These agreements were focused, among other things, on the elimination of import barriers for certain products.

“The invasion of imported products has disrupted our activities, seriously impacting our work,” he laments.

These impacts are still felt today.

To adapt to this reality, Ligali plans to diversify his know-how.

In addition to shoemaking, he plans to make homemade stoves that run on propane gas.

An initiative, according to him, which demonstrates his ability to innovate and persevere.

Despite the challenges, Ligali remains deeply attached to Haiti.

“I love this country, and I don’t plan on leaving,” he says.

Shelf with different Ligali products. December 2024| ©Lucnise Duquereste

In nearly 50 years, he has settled here, where he is married and a father of five children, all born and living in Haiti. His wife, originally from Jacmel, also lives in the country.

Ligali does not travel much between his native land and Haiti.

“My last trip to Nigeria was in 1990,” he says.

As for his citizenship, Sakariyawu Ligali confides that he has never been naturalized.

I love this country, and I don’t plan on leaving

“I always work with my resident permit, and that has never been a problem for me,” he explains, with the serenity of someone who has found his place in a country that he now considers his own.

“M sèlman pa vote. Men apresa, mwen enplike nan tout sa k ap pase nan peyi a. Mwen aprann istwa l. Ayiti se yon pati nan lavi m,” concludes Ligali in a subtly African-sounding Creole, optimistic about the future of the country, which he hopes will one day emerge from its many crises.

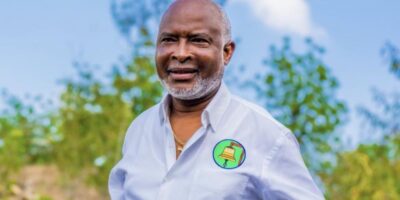

Cover image:Nigerian artisan Sakariyawu Ligali in front of his workshop in Turgeau in December 2024. | ©Lucnise Duquereste

► AyiboPost is dedicated to providing accurate information. If you notice any mistake or error, please inform us at the following address : hey@ayibopost.com

Keep in touch with AyiboPost via:

► Our Channel Telegram : Click here

► Our Channel WhatsApp : Click here

► Our Community WhatsApp : Click here

Comments