Unlike MINUSTAH which left after 13 years of continuous presence on the Haitian territory, MMAS has the distinction of not being a typical UN peacekeeping mission.

The Haitian government wants to transform the Kenyan mission into a United Nations force through a formal request to be submitted in December.

This restructuring should address the financing, equipment and personnel issues facing the existing mission.

It will also come with a change in the legal regime whose configuration can be modeled after the United Nations Mission for the Stabilization of Haiti (MINUSTAH) from 2004 to 2017.

In the meantime, the United Nations Security Council extended the Multinational Security Support force’s mandate for an additional year, until October 2, 2025.

The MMAS, which has been in Haiti for three months, is the second international force to intervene in Haiti after the United Nations mission, authorized in July 2004, in accordance with the agreement adopted by the Security Council under resolution 1542.

This controversial mission was responsible for supporting the disarmament of armed groups and restoring public and institutional order following the fall of President Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

The Kenyan-led MMAS in Haiti, approved in October 2023 by the UN Security Council, is part of the agreement signed between the Haitian and Kenyan governments in June 2024.

This force must fight alongside the Haitian National Police against armed gangs, who have driven more than half a million people to flee their homes, while killing and raping hundreds more.

Read also: Tensions between Haitian police and Kenyans

“These two missions share the same jurisdictional status,” James Boyard, an expert in international law, explains to AyiboPost.

Although the two agreements are similar in several fundamental respects, they diverge in other crucial areas.

These two missions share the same jurisdictional status

Three specialists consulted by AyiboPost consider the implications of these parallels, particularly with regard to the management of potential abuses and the obligations of the parties involved. These comparisons provide insights into what a new United Nations mission in Haiti could look like.

Unlike MINUSTAH which left after 13 years of continuous presence on the Haitian territory, MMAS has the distinction of not being a typical United Nations peacekeeping mission. It is a mission under the purview of the Security Council, led by Kenya, a member of the UN.

Read also: A look back at 15 years of UN failures in Haiti

However, the status of forces agreement (SOFA) signed as part of the deployment of the MMAS in Haiti, grants immunity to mission personnel and local contractors as they carry out their duties.

No member of this mission, currently made up of around 400 Kenyans, 20 Jamaican soldiers and 4 police officers, as well as 2 soldiers from Belize, can be imprisoned in Haiti.

According to the document, any criminal legal proceedings will be conducted in the country of origin of the officer involved.

In addition, a member of the mission apprehended in flagrante delicto must be handed over to the mission without delay for further action.

“This force [the MMAS] enjoys absolute jurisdictional immunity,” comments James Boyard.

For its part, in 2004, MINUSTAH enjoyed full immunity under the February 13, 1946 convention, as a subsidiary of the United Nations.

“The MMAS, unlike the MINUSTAH, is not a subsidiary body of the United Nations and should not enjoy all immunities,” concludes Professor James Boyard who nevertheless recognizes that the principle of immunity from jurisdiction is intrinsic to the nature of this type of mission.

Regarding customs tariffs, the forces revenues are not subject to taxation in Haiti.

“MMAS, unlike MINUSTAH, is not a subsidiary body of the United Nations and should not enjoy all immunities”

Members of the MMAS, as was the case for the MINUSTAH, cannot be arrested and are not liable to trial before the Haitian courts for acts committed in the exercise of their functions, including their words and writings, notes Ricardo Augustin, doctor in Political Sciences and International Relations.

Dr. Ricardo Augustin, in his office: July 10, 2024 | © Fenel Pélissier

The effects of this immunity extend even after the departure of the members of the mission or at the end of its mandate.

Other points bring the two agreements closer together.

The MMAS, like the MINUSTAH, may have its own means of communication such as radio stations to broadcast information concerning the activities of the mission.

Freedom of communication is guaranteed in compliance with Haitian laws governing the matter. The freedom to come and go is guaranteed.

MMAS vehicles are not subject to Haitian regulations regarding registration and certification as was the case for MINUSTAH vehicles.

However, they must have insurance coverage.

Certain substantial elements differ between the two missions.

The MINUSTAH was initially established for a period of six months, while the MMAS was established for an initial period of one year.

The MINUSTAH comprised a civilian and a military component, while the MMAS is made up of police units.

In the event of a dispute or claim for damage attributable to the mission, the agreement pertaining to the MINUSTAH provided for a more detailed procedure, underscores Ricardo Augustin.

For the author of “Voter autrement en Haïti,” the dispute resolution mechanisms are more elaborate in the agreement signed with the MINUSTAH than in the MMAS agreement.

With the MINUSTAH, a permanent complaints commission was created by the agreement.

This commission was responsible for ruling on any dispute or claim arising under private law.

It intervened in cases that did not relate to damage attributable to the operational imperatives of the MINUSTAH.

The MINUSTAH or one of its members was a party to these disputes, over which the courts of Haiti had no jurisdiction.

The agreement signed between the MINUSTAH and the Haitian government even provided that a dispute relating to the interpretation or application of the agreement could be submitted to an arbitration tribunal composed of three members.

According to Ricardo Augustin, this provision is not found in the dispute resolution mechanisms of the MMAS agreement.

It is stipulated in this agreement that “any dispute between the Parties concerning the interpretation or application of this Agreement shall be resolved solely through consultation between the Parties.”

However, says Augustin, the agreement remains silent on the course of action if the Parties fail to find a solution through consultation.

On the other hand, it states that the immunities and privileges granted to members of a United Nations mission are essential to enable them to exercise their functions optimally.

However, this does not exclude the right of the host state to exercise control over their use in order to prevent irreparable damage.

It is also expected that the government will establish customs facilities for the receipt of materials, equipment and any other items intended for the Mission.

For some, the MMAS structure poses a problem.

Benin, initially committed to providing 2,000 soldiers, is now reluctant to deploy its forces to Haiti, citing its refusal to place its soldiers under the command of Kenyan police officers.

At the beginning of September, Haitian authorities as well as international actors, notably Ecuador and the United States, raised the possibility of converting this mission into a peacekeeping operation under the United Nations umbrella.

Visiting Haiti on September 21 before flying to the 79th session of the UN General Assembly, Kenyan President William Ruto expressed his support for this reorientation.

Missing elements from the June 2024 agreement are a concern for Ricardo Augustin.

According to him, the agreement concluded with the MMAS does not provide any protection for the Haitian State in the event of serious harm to the civilian population caused by the actions of members of the Mission.

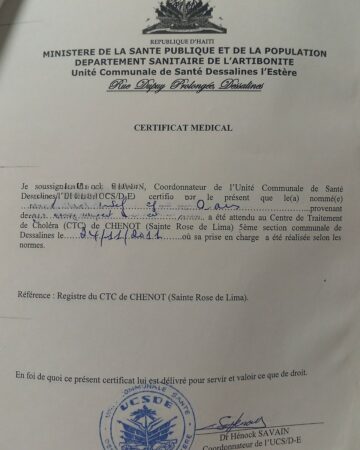

For the university professor, the cholera epidemic introduced by the MINUSTAH does not seem to have served to prevent such occurrences. More than 10,000 Haitians died.

Cholera victim medical certificate.| © Fenel Pélissier

Given that a commission of inquiry is planned to examine cases of criminal offenses committed by MMAS members, Ricardo Augustin believes that it is the responsibility of the Haitian government to actively participate in any investigation.

“The participation of civil society at all stages of the investigation is essential,” he maintains.

“It is imperative for the Haitian side to be able to produce solid documentation with irrefutable evidence for all jurisdictions,” recommends Augustin.

For James Boyard, author of the book « le Procès de l’Insécurité: Problèmes, Méthodes et Stratégies, » the two agreements are similar in the way they deal with cases of human rights violations.

Furthermore, the specialist warns of their disregard for humanitarian rights.

These principles apply specifically in times of war or armed conflict, to protect those who do not participate in hostilities.

They aim, among other things, to prohibit deliberately targeting non-combatants, care for the wounded and sick, and respect for cultural property.

“I do not understand why the question of violations of humanitarian rights was not taken into account in this agreement, when the potential exists every time there is an armed conflict,” Boyard told AyiboPost.

This is not new. “In 2004, this question was not taken into account either, because the peacekeeping forces were not intended to act in a repressive manner in a context of armed conflict,” offers the specialist.

In the context of armed conflict, these forces generally act as interposition forces.

For Boyard, the current context is different and therefore requires a different approach.

“Today, we are not in the pattern of interposition but of fighting against bandits in a repressive manner,” details Boyard.

In the event of a violation of humanitarian rights, the court of the offender’s country of origin is not the only party with the jurisdiction to try the case, but also any court in other countries that have ratified the convention.

In 2016, the former Secretary-General of the United Nations, Ban Ki-moon, recognized the involvement of the UN in the spread of the cholera epidemic, introduced 6 years earlier in Haiti and responsible for more than 820,000 infections.

The mission has been accused of committing dozens of cases of human rights violations in Haiti.

In an interview with AyiboPost, Mario Joseph, attorney from the Bureau of International Lawyers (BAI), does not rule out the possibility of new human rights violations, and fears that acts similar to those of 2004 will go unpunished.

Me Mario Joseph at his Cabinet: July 12, 2024 | © Fenel Pélissier

Article 55 of the country agreement of July 9, 2004 provides for a permanent complaints commission created for this purpose to rule on any dispute or complaint falling under private law, however this commission has never been established, stresses Me Mario Joseph.

Despite the implementation of this procedure, he adds, it has been difficult to obtain compensation for the victims of cholera as well as for the mothers of children abandoned by UN peacekeepers.

Cover image: MMAS soldiers (left) MINUSTAH soldiers (right) Collage: AyiboPost | © Guerinault Louis/Anadolu via Getty Images – Council on Hemispheric Affairs

► AyiboPost is dedicated to providing accurate information. If you notice any mistake or error, please inform us at the following address : hey@ayibopost.com

Keep in touch with AyiboPost via:

► Our channel Telegram: click here

► Our Channel WhatsApp: click here

► Our Community WhatsApp: click here

Comments