« As soon as the white people saw that Haitians were renting or buying homes near theirs, they gradually moved away, » explains Sylvie Pognon. This small town only had 4,000 residents when Haitians started arriving

By two o’clock in the afternoon, we arrived in Mount Olive, a small town in North Carolina. The trip lasted an hour and took us to the heart of rural America, that of the farmers, the ones who vote Republican.

Haphazardly, we headed to meet some Haitians because they seemed to be many in this small city. And as fate would have it, after more than an hour of turning in circles, we found ourselves in front of the God’s grace Convenience Store.

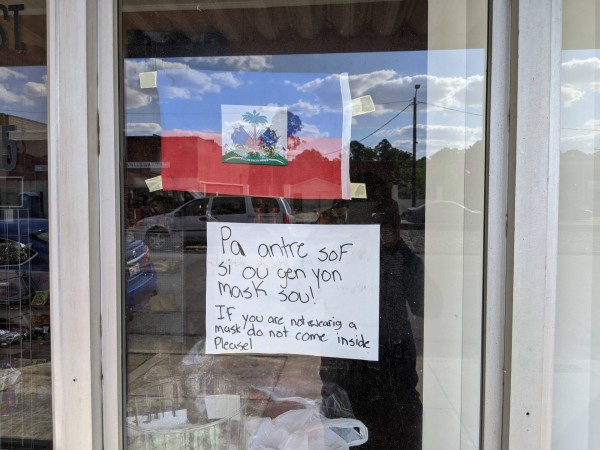

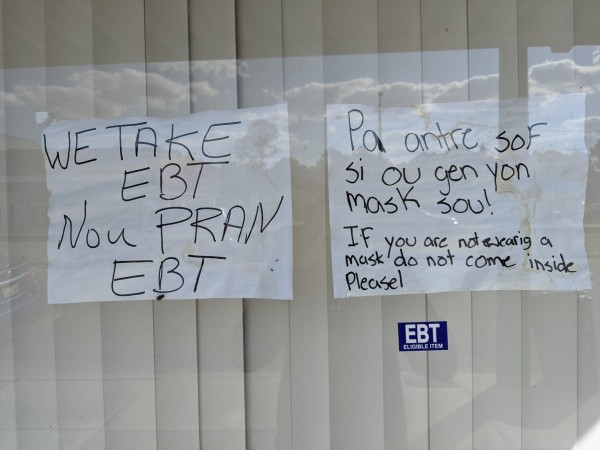

It’s open. It won’t close until nightfall. On the window that reveals slivers of the interior, someone has put a Haitian flag, fixed with adhesive tape. That’s what caught our attention. Next to the two-tone, there are inscriptions in English and Creole. No face mask, no entry. This warning seemed to be there because it had to be. But no one or nearly no one among those we saw entering the store paid it any mind. With their faces uncovered, customers got out of their cars, rushed inside, did their shopping, and quickly left, after having a short conversation in Creole with the store owner, Jaccius Clairmond.

Right in front of the store, main street. Quite literally, the main street. A long railroad is there as a reminder that trains still run in this small town. The street was quiet. Shirtless children sat near a Latino store. Cars drove by every now and then, and most of the drivers were Black people. Not necessarily Haitian. But they could’ve been.

Inside Jaccius Clairmond’s store, security cameras scanned the shelves. The owner was in deep conversation with a customer who owed him 30 USD. « I have already paid you back, case closed, » she replied. Clairmond was not convinced but let it go. An old woman came in, rummaging through the shelves, and returned a minute later complaining that she couldn’t find potatoes for a « patat ak lèt ». A man asked for powdered djondjon, not cubed. We are not depatriated.

Jaccius Clairmond opened his store two years ago. But a few years earlier, in 2010, he was in this same town in a three room apartment with 34 other people. He had come from Florida to settle in this small shabby town. As opposed to many of his compatriots, he still lives there.

According to the U.S. Census Office, in 2010 there were approximately 4,000 people living in Mount Olive. And among those residents, there was not a single Haitian person. That changed dramatically when more than 3,000 Haitian migrants arrived in the small town from one day to the next, with no warning.

Clairmond is part of the first group of migrants to arrive. The native of Limonade had been living in Florida since 2006. They were only 11 Haitians to come to Mount Olive. « There were no job opportunities in Florida, and the cost of living was high, he says. A factory in Mount Olive that needed workers sent people there to be employed. The Americans didn’t want those jobs. I didn’t know anyone there, but I didn’t hesitate a moment to make the trip. »

The factory in question is Butterball LLC, a company that produces poultry, specifically turkeys. But the conditions touted by the broker weren’t really accurate. « When we arrived, we were placed in a three room apartment where 24 other people were already living. We slept on the floor the best we could. »

For two months, Jaccius Clairmond worked at Butterball and lived in this crowded house. He was paid 9 dollars an hour. Shortly after, this wage would be adjusted to $10.87. It is a tough and dangerous job. He also left his wife and 12-year-old son in Florida, as did most of his peers.

A few months later, his wife joined him when he and two other friends decided to rent a new house together.

Later, following these first eleven pioneers, the flow of migrants did not stop. They all came to look for work, at the Butterball factory or in other companies in the region that did the same type of work. But some of them had difficulty integrating.

Sylvie Pognon owns a thrift store on the main street where you can buy anything, including clothes, at affordable prices. She remembers those first moments, which she did not experience, but which her husband, Pastor Pierre Pogon, shared with her. « Many of them did not speak English and could not communicate effectively. They did not have a car, in a city where you need one to get around. They carried their dirty clothes on their heads to the laundromat. It was a difficult time. »

In any case, Haitian migrants have breathed life into the quiet, almost boring place that Mount Olive used to be. Before the Haitians, in the 2000s, Latinos had come here for the same purpose. But they soon left, as they were unwelcome. For the Haitians, it was different. « We were very well received, says Jaccius Clairmond. People helped us, especially when the other groups of Haitians arrived. »

A few years later, in 2021, the situation had changed. Many Haitians have left. « Mount Olive was the first place where Haitians settled in North Carolina, » explains Sylvie Pognon, but they soon left for other major cities because they received better salaries. «

Those who remain no longer really constitute a community. « To find a group of two Haitians, you have to go to church on Sunday. That’s the only place where there is a gathering. We don’t have anything that brings us together, like a party, not even the celebration of the flag. »

In addition, rents have increased, and Sylvie Pognon believes that Haitians are largely responsible. It’s also one of the reasons why they went elsewhere. « In 2012, for example, rents were low. You could buy a house for $70,000, even if there were repairs to be made. Now, that’s not possible. »

Although no longer in Haiti, some undesirable behaviors are still present among compatriots, making the idea of a community even less possible. « It’s sad, but I have clients who have debts and refuse to pay, says Jaccius Clairmond. They prefer to choose not to talk to me than to pay their dues. This store requires a lot of money. I buy my products in Florida, and the cost to get there and back is expensive. Every quarter I pay at least $1,000 in taxes. But they don’t seem to understand that. »

Things almost came to a head when young Haitian men from Florida started getting involved in delinquent activities in Mount Olive. « At first, the parents came alone, and their children lived in Florida, says Jaccius Clairmond. But when their situation improved, the kids came. Or some came because they had friends here. Some of them were into stealing, and they were doing it to the detriment of their Haitian compatriots. »

« The way Haitians are perceived has started to shift because of these young people. When we came here, some neighborhoods didn’t have enough police officers, says Sylvie Pognon. But when these young people started committing these acts, reinforcements arrived. I remember they kidnapped a Haitian lady. They took her debit cards and emptied them. They robbed her house. It was horrible. »

Most were arrested or deported to Haiti, and the rest fled the city. But the way other Mount Olive residents view Haitians has begun to change. « Moreover, even if it doesn’t look like it, there is racism. As soon as the white people saw that Haitians were renting or buying homes close to theirs, they gradually moved away. »

English translation by Didenique Jocelyn.

This article is part of AyiboPost’s exploration of Haitian migration. Click HERE to read the reports, expert perspectives and watch the documentaries.

Comments