The hemorrhage of professionals is slowly killing the country’s institutions

Extrac Group, a company which offers services in technology and web-based communication, finds itself severely hindered since its chief administrator left for the United States in 2021.

Ralph Fleuristil, the institution’s deputy administrator, says he is having trouble replacing the leader, who is also a qualified computer scientist, but immigrated “because of insecurity”.

The survival of Extrac Group is now in question. “I’m having a hard time running the institution, says Fleuristil. He was the engine and his skills helped us to attract many customers,” he complains.

Thousands of professionals, young and old, have left Haiti over the past three years due to worsening insecurity.

“This is one of the main problems that most universities in Haiti are now suffering from, according to economist Thomas Lalime. With the departure of some professors, classes are no longer scheduled.”

In addition to the decline in business turnover, which certainly affects the country’s gross domestic product, this situation’s impact on the quality of education is sizable. “Universities are training and graduating students who are less competent for the labor market,” continues Lalime.

In 2021, nearly 37 highly qualified executives from the central bank left Haiti to settle elsewhere. This information was reported by the governor of the Central Bank of Haiti (BRH), Jean Baden Dubois, during a broadcast on a television station in the capital earlier this year. “The situation is the same for other commercial banks in the country,” he says.

These executives’ know-how cannot be replaced overnight. For someone with a Master’s degree in money and banking who, after ten years of experience, decides to leave, the loss is great for the central bank.

Haiti is one of the countries most affected by the brain drain.

According to a study entitled “Emigration and Brain Drain: Evidence from the Caribbean” (2006), published by the International Monetary Fund, the university enrollment rate in Haiti is just under 1%, whereas 84% of university graduates have left the country.

However, this situation is not new to Haiti, since under the Duvalier dictatorship at the end of the 20th century, many persecuted professionals and intellectuals were forced to leave the country.

The ongoing exodus also has an impact on non-governmental organizations (NGO), which are the main substitutes for the government in localities, supporting local populations on the margins of disaster.

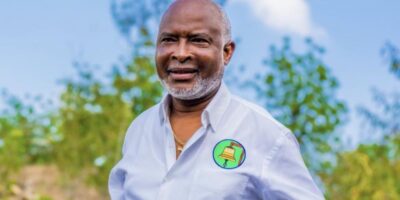

Agronomist Jhonson Monestine was hanging on to his position at the Centre for International Studies and Cooperation (CECI), a Canadian NGO, until the director of the organization was kidnapped. He was only released after the payment of a ransom of $750,000 US dollars.

The former executive at the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) permanently relocated to the United States on December 22, 2021. He joined his wife and two children who emigrated the year before.

“I wanted to build a house on a piece of land I had purchased, » says Monestine. “I backed out.”

Replacing the eight-year professional who was receiving more than 200,000 gourdes per month as salary is not an easy task. That is why, despite his absence, he continues to get calls from the NGO.

Like most Haitian professionals now abroad, Monestine worked outside the Port-au-Prince metropolitan area.

In truth, some of these professionals do not leave the country due to a lack of jobs or salary issues.

“They are looking for an improvement in their living conditions and personal development, explains economist Enomy Germain. The Haitian environment is impervious to life,” says the expert.

Haiti lacks resources but funds the development of other countries through its human capital. “This is a loss for the country since it has less and less capacity to start its own development process,” continues Germain.

Economist Thomas Lalime adds nuance to this position. Most of these professionals have difficulty integrating their field of work elsewhere, he says. “A lot of times they are forced to take odd jobs when most of them were recipients of state scholarships.”

The first few years in the United States are not easy. With no legal status and no job, most migrants spend the little money they had saved in Haiti.

This is the case for agronomist Monestine, who lives in the United States. “My wife was lucky enough to get Temporary Protected Status (TPS), he says. She now works as a beautician in a beauty salon.”

Before leaving Haiti, the woman, who has a degree in tourism administration, worked on a beach on la côte des Arcadins.

Monestine is holding on thanks to an investment he made in a transportation company owned by his brother.

Jonas Laurince, a journalism professor at the Université Notre Dame d’Haiti (Notre Dame University of Haiti) also resides illegally in the United States. “I’ve sometimes gotten odd jobs that have allowed me to take care of my family. But I don’t have a real job because I don’t have a work permit yet,” Laurince confides.

The small amount of money he received enabled him to contribute to the expenses of the house where he lives with his family in the United States.

Laurince worked with several NGOs in Haiti after graduating from the State University of Haiti (UEH) with a degree in social communication. His decision to leave the country with his family members dates back to 2019, after the weeks of “pays lock”.

The public administration has lost many people in recent years.

Elie Jean Philippe was coordinator of the public service within the Office of Management and Human Resources (OMRH). He currently works at the technical secretary’s office of this entity which manages the government’s personnel.

According to Philippe, the brain drain problem in the public sector is due to the lack of safety on one hand, and the salary issue on the other.

“The current system in public administration does not encourage the employee to perform well, says Philippe. Within public administration, there is no criteria for getting promoted. Promotions are political.”

With inflation and the collapse of the economy, the government payroll will not necessarily change. This will evidently push competent professionals even further away.

At a maternal and child clinic at La Fossette Health Center in Haiti, patients arrive for regular check-ups as well as vaccinations. Photo by Angela Rucker / USAID

English translation by Didenique Jocelyn and Sarah Jean.

Comments