To survive in Haiti most journalists confirm having implemented strategies to protect themselves, which ultimately result in journalistic reports lacking sensitive information likely to disturb gangsters and powerful members of government

Lire la version française de cet article ICI.

Marc-Henry, a journalist, works at Radio Télévisons Caraïbes (RTVC). “On several occasions I had to refrain from communicating certain information because it can be excessively costly” he says.

Jerry is a Radio Sans Fin (RSF) collaborator. His strategy is to avoid controversial topics that may anger some. “We have to be aware of the neighborhoods we frequent and their dynamics, watch out for the people concerned by our work and avoid hinting at certain influential individuals in high places” he explains.

Kidnapping, rape, armed attacks, murder or even massacres…the news has been dominated by generalized insecurity in all forms for several months now in Haiti. In a report released last December, the National Network for the Defense of Human Rights (RNDDH) notes that at least 525 people lost their lives due to insecurity in Port-au-Prince.

Read also: Ce journaliste a reçu une balle en plein œil. Il revient à la charge.

Press workers also find themselves grappling with this climate of terror. Access to information which was already difficult is becoming almost impossible for certain sensitive topics. To survive most journalists state having implemented strategies which ultimately result in journalistic reports lacking sensitive information likely to disturb gangsters or powerful members of government.

Access to information which was already difficult is becoming almost impossible for certain sensitive topics.

“Part of the population is aware of it” analyzes lawyer Samuel Madistin, referring to this situation. He recalls the case of photojournalist, Vladimir Legagneur, who has been missing in Grand-Ravine for almost three years now. “The task is not easy for human rights organizations either” underlines the Fondasyon Je Klere activist.

A Constant Challenge

Marc-Henry lives between Fontamara and Martissant (two suburbs in the capital). With the rise of insecurity in the streets getting to the RTVC headquarter in downtown Port-au-Prince is a constant challenge for this professional. He explains that “for three to four years there has been no police presence” in the so-called lawless zone where he lives.

Some media have taken security measures and sometimes install cameras on their premises. Foreign institutions offer their journalists some protective equipment. However, for most locals the “save yourself” principle is still in order. On all social networks, even going as far as his WhatsApp profile, Marc-Henry exposes himself as little as possible.

Read also: Pour le journaliste haïtien, la violence vient d’abord de la police

Above all, the young journalist does not want the inhabitants of his area, let alone the gangsters, to know his profession. For this reason he never wears the media jersey in his neighborhood nor does he show his press identification card all the time because his primary concern remains his safety. “I’m not saying [the gang members] don’t know about my work; they have goons to keep them informed of everything. Yet, I try to expose myself as little as possible.”

Marc-Henry makes sure he never has to deal with topics linked in any way to Fontamara or Martissant. In any case, “it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, for a person to show up without warning thinking that they will accomplish any work” informs Marc-Henry. For any report it is necessary to have previously negotiated with the gang leader of the area in which we intend to work for his approval.

The RTVC journalist recognizes working on the degradation of his neighborhood’s public square would be interesting. He would have liked to take on a report like this, but the risk of being exposed by the gangs of Fontamara is far too great.

Repeated Victims

The tentacles of insecurity also reach journalists who do not report on insecurity-related issues or political news. Pierre, the editor of Symbiose, an online platform, says he has been evolving in the cultural sector since 2018. He has not covered any nightlife activity since the rise in insecurity in the Haitian capital. This decision was taken “in agreement with the platform’s management”.

Several press workers report being victims of widespread insecurity. Michel Joseph is a news anchor at RTVC. He confirms having already been robbed in the streets.

Lire également: Des bandits attaquent cette journaliste à Grand Ravine. Son média l’abandonne.

Increasingly, the bullying comes from the authorities. “Journalists are also in danger when policemen are around” says Jerry of Radio Sans Fin. The reporter confides feeling threatened when he must work with police officers in the area. This feeling has persisted since he was openly attacked by an agent from the General Security Unit of the National Palace (USGPN).

“I was filming USGPN agents pointing their guns at students from the École normale supérieure (ENS) who were leading protest movements says Jerry. It was then that one of the agents approached me to ask me to give him the phone I was filming with. I presented my press pass and refused to hand over my cell phone, but he simply ignored my badge and proceeded to attack my phone which he broke completely. »

Media Justice

Despite everything, journalists are increasingly in demand. Almost every workday, citizens, sometimes dozens of them, gather in front of the RTVC premises to denounce acts of violence perpetrated on their relatives. The “complainants think they can find help from the press instead of the police” says Marie Rosie Auguste of RNDDH.

With repeated strikes for which it bears the brunt “justice has hardly worked for 3 years” specifies the lawyer, Samuel Madistin. In addition, the institution suffers from an aggravated loss of confidence. “Scandals of corruption, influence peddling and illegal appointments are unfortunately characteristic of the Haitian judicial system. »

Also, the people avoid the justice system as “access is too costly” and run to a press that cannot provide any real answers. As a last resort, they have preferred to try their matters in the court of public opinion instead of bearing their cross in silence. For Marie Rosy Auguste, this still constitutes “a social sanction imposed in the absence of a judicial one”.

Insecure or not, the radios continue to talk, television networks continue to work, and the online media are still in operation. But what information are they relaying exactly?

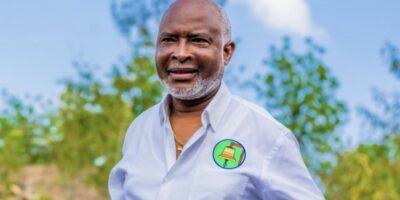

Rebecca Bruny

Comments